by Climate Discussion Nexus, Aug 28, 2025 in ClimateChangeDispatch

Disasters don’t count if you don’t count them.

According to its publishers, a dataset called EM-DAT, which stands for Emergency Events Database, so it’s not even an acronym, lists “data on the occurrence and impacts of over 26,000 mass disasters worldwide from 1900 to the present day.” [emphasis, links added]

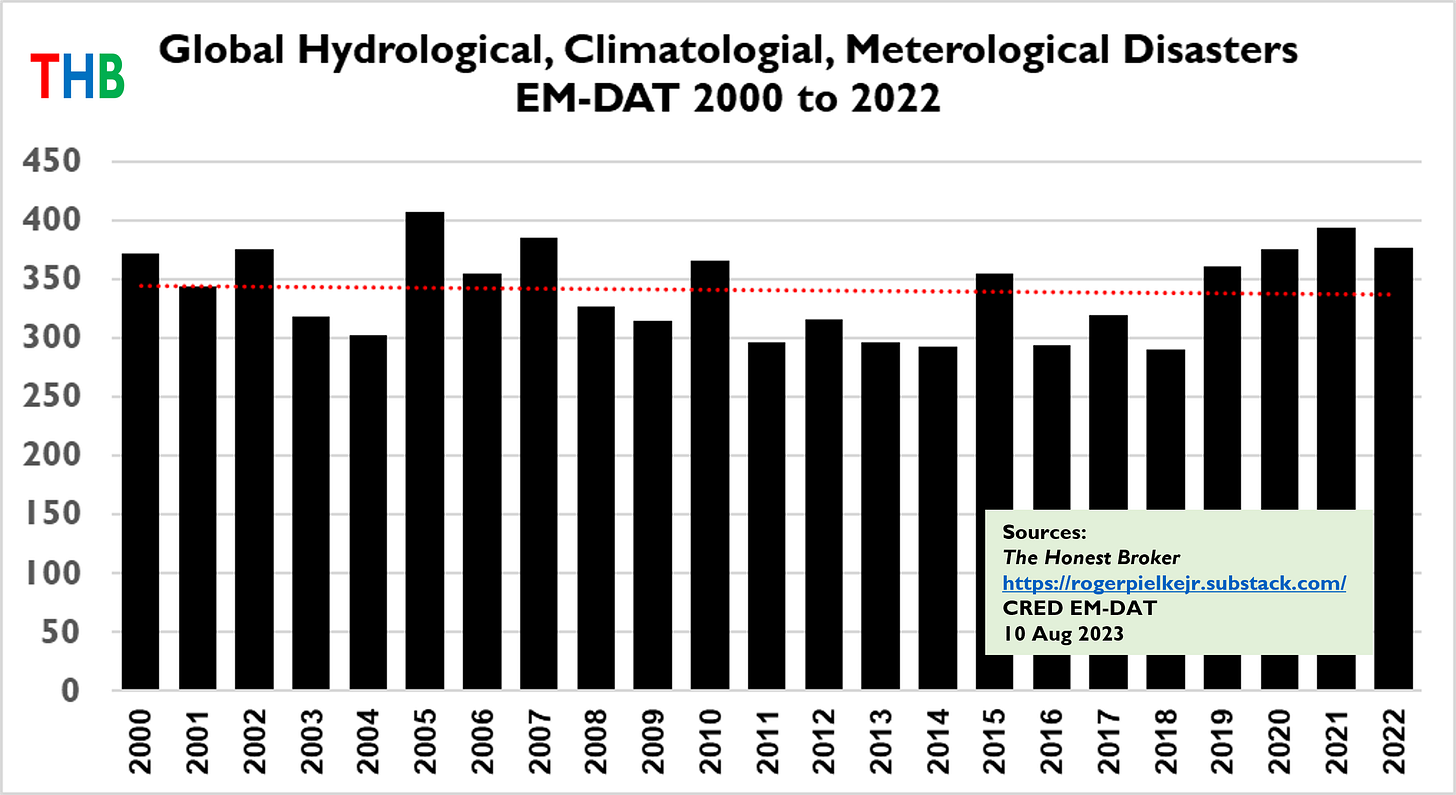

Which makes it perfect for studying long-term trends. And what’s even better, for the climate change crowd anyway, is that, as the authors of a 2024 study noted, “There are very strong upward trends in the number of reported disasters.”

But as the same authors noted in the very next sentence, “However, we show that these trends are strongly biased by progressively improving reporting.” Simply put, before 2000, reporting of small disasters that caused fewer than 100 deaths was hit-and-miss.

So, historically, the record of giant disasters that killed hundreds or more persons is reasonably complete, but not the record of small ones.

And the authors of the recent study argue that once they adjust for the effect of underreporting, the trends in disaster-related mortality go away.

The paper, “Incompleteness of natural disaster data and its implications on the interpretation of trends,” by a group of scientists in Sweden, began by noting that they are not the first to point out the problem.

The weird thing is that many authors who have pointed out this massive flaw have then gone ahead and used the data anyway, as though it did not exist, or at least they had not noticed it:

“Various authors (Field et al., 2012; Gall et al., 2009; Hoeppe, 2016; Pielke, 2021) have noted that there are reporting deficiencies in the EM-DAT data that may affect trends then proceeded to present trend analyses based on it without correction. Even the EM-DAT operators themselves discourage using EM-DAT data from before 2000 for trend analysis (Guha-Sapir (2023)). Yet recently, Jones et al. (2022) investigated the 20 most cited empirical studies utilising EM-DAT as the primary or secondary data source, and found that with only one exception the mention of data incompleteness was limited to a couple of sentences, if mentioned at all.”

Having made that point, their study then digs into the records and shows that in the post-2000 period, there is a steady pattern relating the frequency of events to the number of fatalities (F) per event.

It follows something that statisticians call “power-law behaviour” in which the more extreme an outcome, the rarer it is, not in a straight line but in an inverse exponential relationship, where extreme things, [like] large numbers of fatalities in a disaster, are a lot rarer than small numbers on a logarithmic curve. (For instance, in boating accidents, there are tens of thousands of individuals falling out and drowning for every Titanic.)

Hydrological, meteorological, and geophysical disasters all follow power-law behaviour in recent decades. But in earlier decades, the relationship doesn’t appear to hold because of a deficiency of low-fatality disasters in the data, rather than because it wasn’t still true then..

…