by C. Graling, Sept 24, 2025 in ScienceNews

A January earthquake swarm exposed shared plumbing between Santorini and Kolumbo.

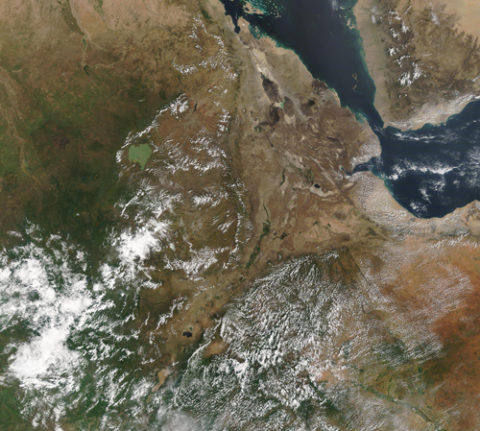

An intense swarm of earthquakes around Greece’s Santorini Island in January has revealed a fiery underground link between two neighboring and historically explosive volcanoes.

Analyses of seismic activity from June 2024 through February 2025, along with changes in the island’s surface elevation, suggest that the same well of magma feeding the Santorini volcano may also supply the submerged Kolumbo volcano, just seven kilometers away, researchers report September 24 in Nature.

Complex, shared magma plumbing systems can complicate the interpretation of earthquakes and signs of imminent eruptions, say Marius Isken, a geophysicist at the GFZ Helmholtz Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany, and colleagues. This study, they say, highlights the need for real-time, high-resolution monitoring to improve volcano warnings.

Santorini is known for a catastrophic volcanic eruption around 1560 B.C. that contributed to the end of the Minoan civilization and caused widespread devastation, including earthquakes, tsunamis and possibly a volcanic winter. Kolumbo is no slouch either, erupting most recently in A.D. 1650.

When a swarm of over 1,200 earthquakes rattled the region early this year, Greece declared a state of emergency, fearing an imminent eruption. Although no eruption ensued, the abundant quakes allowed Isken and colleagues to examine the subsurface and better understand how and where magma moved.