by T. Joose, July 25, 2022, in Science

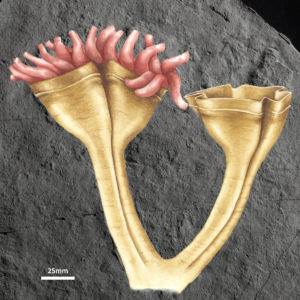

If you visited the oceans more than 500 million years ago, you’d find yourself in an alien world. Beings with quilted folds of soft tissue sat on the seabed like rugs, and life forms that looked like fronded plants but were actually animals made anchor on the ocean floor. But one organism might be somewhat familiar: a stalked, cuplike creature with waving tentacles resembling those of a jellyfish. The newly described fossil of this organism, named Auroralumina attenboroughiiafter naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough, is between 556 million and 562 million years old and may be the oldest example of an evolutionary group still living today.

When co-author and University of Oxford paleobiologist Frances Dunn saw a cast of the fossil, she says, “It was instantly clear that this was really special and really rare.” With other fossils from the Ediacaran period, between 635 million and 541 million years ago, her first impression often is “What is this? How can I relate this to anything that’s alive today?” But with this specimen, she thought, “I know what this is.”

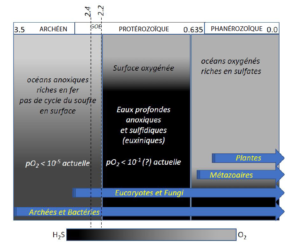

Classical scientific wisdom places the origin of modern animals about 539 million years ago during what’s called the Cambrian explosion. At this time, creatures with specialized tissues, organs, guts, and symmetrical left and right sides—all traits we recognize in the animals of today—began popping up.

…