by P. Gosselin, May 8, 2021 in NoTricksZone

At Die kalte Sonne, Prof. Fritz Vahrenholt – one of the founders of Germany’s modern environmental movement – presents his monthly summary, which includes a look at global temperature and how the models are doing.

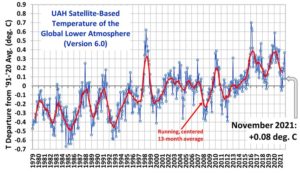

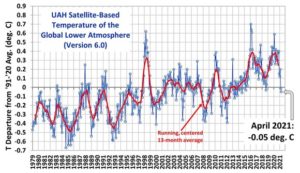

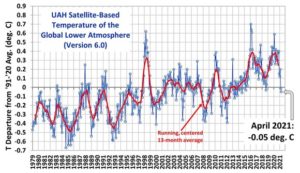

“The global mean temperature deviation of satellite-based measurements from the mean of the 1991 – 2020 period was -0.05 degrees Celsius in April 2021. Nevertheless, German courts have ruled that something has got to be done about the warming planet!

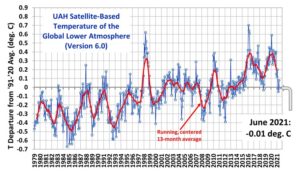

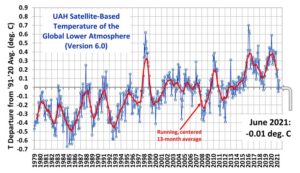

Global temperature curve in April 2021

The cool La Niña situation over the recent months is still having an effect. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), there is an 80% probability that La Niña will end between May and July. However, the agency expects a new La Niña to begin again in the fall.

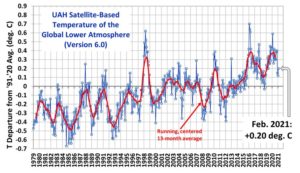

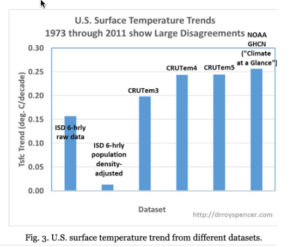

The average temperature increase has been 0.14 degrees Celsius per decade. The model calculations, on which the IPCC’s recommendations are based, come up with a temperature increase that is twice as high for the same period (see chart below, source: R. Spencer 2021).

This striking deviation from the real temperature development is politically significant, because model forecasts are the basis for far-reaching decisions, such as constitutional court rulings.”

…