by A. May, 4 August, 2025 in WUWT

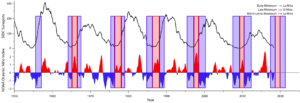

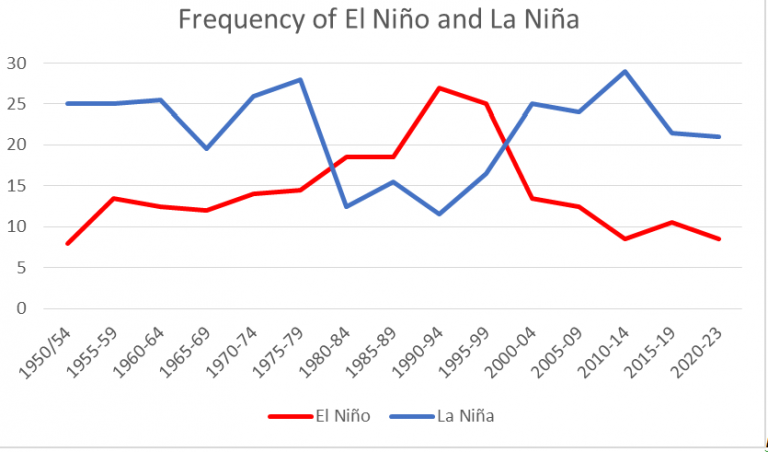

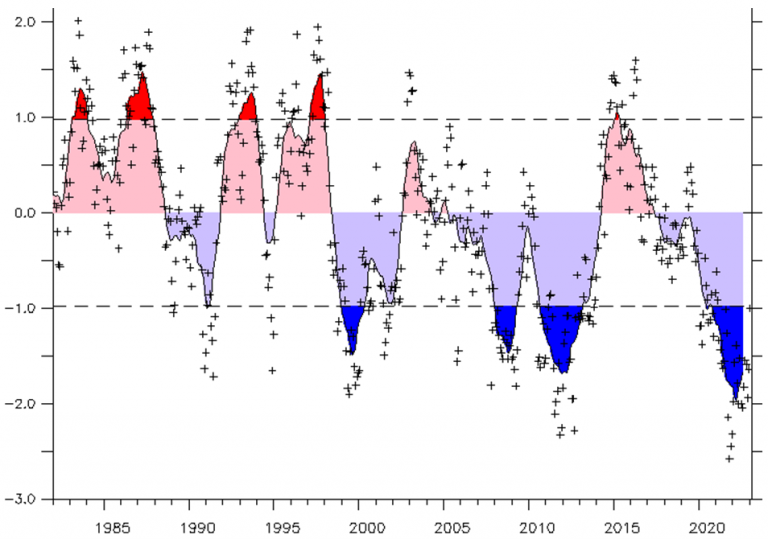

The Oceanic Niño Index or ONI is NOAA’s primarily indicator for monitoring the sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly in the critical Niño 3.4 region. It is a 3-month running mean of ERSST.v5 SST anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region, defined as 5°N-5°S and 120°W-170°W. Figure 1 shows the ONI as computed from the NOAA ERSST dataset. ERSST is a two-degree gridded dataset, so the region averaged for figure 1 is 6°N-6°S and 120°W-170°W.

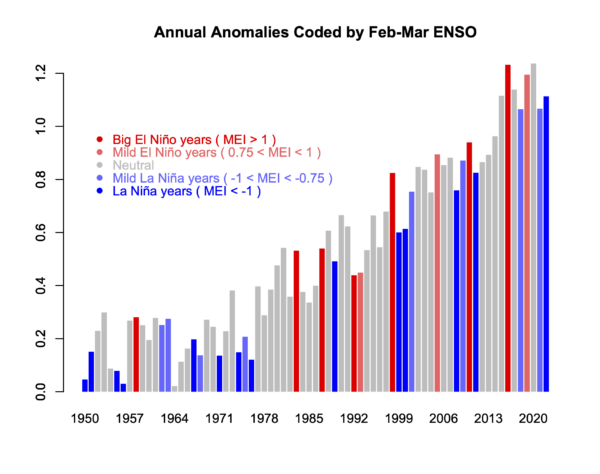

The current ENSO state, as of July 2025, is ENSO neutral, with an average ONI of about zero. NOAA prefers to use a base period for their ONI anomalies of 1991-2020, but we use 1961-1990 to be consistent with the other posts in this series and with HadCRUT5. There is a visual trend over the past 175 years, Niños are more common now and stronger than in previous years. Climate models have a very hard time duplicating ENSO over both short and long periods of time (IPCC, 2021, p. 115). The Niño 3.4 region is shown in figure 2 in red.

…

Figure 1: UAH global temperature anomaly

Figure 1: UAH global temperature anomaly