by P. Keeney, Oct 27, 2025 in ClimateChangeDispatch

Among all the discussions about climate change, one aspect of the debate gets far too little attention: the moral and practical costs that climate alarmism places on the developing world. [emphasis, links added]

For those in the West, energy is so plentiful that it’s almost invisible. We flick a switch, start a car, or refrigerate food without considering the miracle of power that makes it all possible.

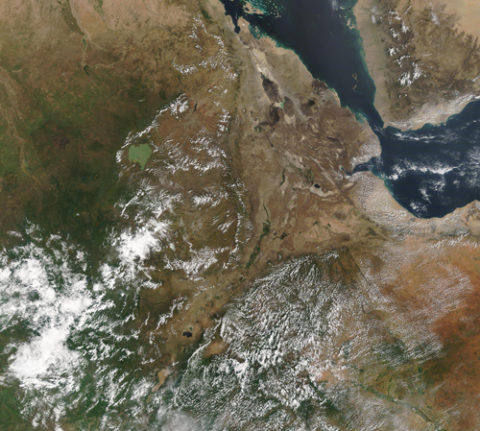

But for billions of people in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America, energy is not just a convenience in the background; it’s the difference between subsistence and progress, between darkness and light, between education and ignorance.

It is easy for comfortable Westerners to moralize about “ending fossil fuels.” For the world’s poor, that slogan means ending development itself.

Wind and solar can supplement power in modern economies, but they cannot satisfy the needs of industrialization. A solar panel may charge a phone or light a hut, but it cannot operate a factory, a hospital, or a modern water system.

The idea of “leapfrogging” fossil fuels and moving straight to renewables is delusional.

As Danish economist Bjorn Lomborg points out in his book “False Alarm,” a solar panel:

“can provide electricity for a light at night and a cell phone charge, but it cannot deliver enough power for cleaner cooking to reduce indoor air pollution, refrigeration to keep food fresh, or the machinery needed for agriculture and industry to lift people out of poverty.”

For the rural poor in Africa or South Asia, what they need is not less energy but more reliable, affordable, and plentiful energy similar to what the West has long enjoyed.

Yet Western governments and financial institutions have become increasingly obstructive. Under pressure from climate activists, the World Bank and other lenders have reduced fundingfor coal and natural gas projects—the very fuels that helped Western countries prosper.

Wealthy nations, which industrialized through the use of fossil fuels, now refuse the same opportunity to others. It’s a form of moral imperialism: a policy of “Do as we say, not as we did.”

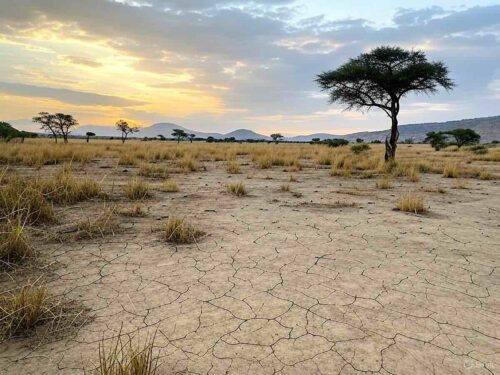

The consequences are significant. In sub-Saharan Africa, around 600 million people still lack electricity. Women cook with wood or dung, inhaling toxic fumes that claim thousands of lives each year.

…