by K. Richard, July 15, 2024 in NoTricksZone

Popular claims that CO2 changes drive temperature changes currently or throughout the distant past “are based on imagination and climate models full of assumptions.”

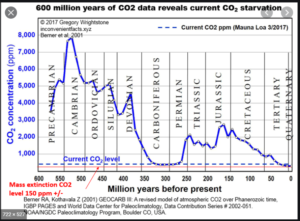

A comprehensive new study details a stochastic assessment determination of the sequencing of CO2 variations versus temperature variations since the 1950s, over the last 2,000 years (the Common Era), and throughout the last 541 million years.

The robust conclusion is that the causality direction – with the understanding that causes lead and effects lag – clearly shows the temperature changes lead and CO2 changes lag on yearly, decadal, and centennial/millennial scales. In other words, “the reverse causality direction [CO2]→T should be excluded.”

The claim that CO2 increases drive temperature changes is thus a “narrative” only, as the claim that “humans, through their emissions by fossil fuel burning, are responsible for the changes we see in climate” can be regarded as a “non-scientific issue.”

The author has had a series of peer-reviewed scientific papers published supporting this same T→CO2 conclusion (Koutsoyiannis et al., 2022, Koutsoyiannis et al., 2020, Koutsoyiannis et al., 2023, Koutsoyiannis, 2024, Koutsoyiannis, 2024) in just the last few years.

Since these papers challenge the prevailing anthropogenic global warming (AGW) narrative so acutely, Dr. Koutsoyiannis has understandably been the recipient of antagonism bordering on vitriol from AGW proponents. This includes comments from peer-reviewers. So, in an apparent effort to foster transparency, he has made the peer reviewers’ comments on this latest paper public. Here is the link to these commentaries:

Peer reviewers’ exchanges with Koutsoyiannis in “Stochastic assessment of temperature–CO2 causal relationship in climate from the Phanerozoic through modern times.”

…