par A. Préat, March 8, 2025 in ScienceClimatEnergie

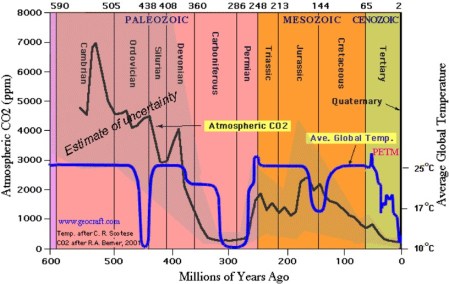

Scotese et al. (2021) have published a remarkable study of the evolution of terrestrial temperatures over the last 540 million years (Ma), i.e. the whole of Phanerozoic time (the Precambrian/Cambrian boundary was set in August 2023 at 538.8 Ma (± 0.2 Ma) based on international chronostratigraphic rules).

It is not possible to discuss this very complete and richly illustrated 127-page article. This article, which is little known outside the sphere of geologists, deserves the attention of a wide audience, because it shows what we have already reported here at SCE (e.g. SCE, 2021), namely that temperature has always fluctuated on Earth (SCE, 2023), that the notion of a ‘regulated or deregulated’ climate is meaningless, and that on the contrary, temperature fluctuations are the rule, often with very large amplitudes (much larger than the current ones), as was the case during the Pleistocene (SCE, 2020). Finally, it is important to note that the current temperature is one of the lowest in the Earth’s Phanerozoic history.

As mentioned above, there is no question of discussing this dense article. Interested readers can read it and see for themselves the methodology, the arguments for interpretation and the conclusions.

I will give here the summary of this article with the three most important synthetic graphs (Figures 1, 2 and 3) showing the evolution of temperature during the Phanerozoic. I then merged the three graphs to present a global view from the Cambrian to the present day (Figure 4). I have also considered a fourth figure (= Figure 5 here) by the authors, which highlights the major geological periods affected by these fluctuations.

Nor is there any question here of discussing the notion of global average temperature, which is even more delicate when it comes to ancient times. This notion has been discussed several times in SCE articles (here, here and here).

In conclusion, yes, temperature varies on different timescales, even short ones, as shown by the Pleistocene. For most periods, variations are also the rule, and future research will clarify the frequencies as temporal precision improves. Let’s not forget that geologists have to ‘fight’ with time scales that are constantly being improved, as temporal resolution becomes increasingly poor or unsatisfactory with the age of the series: today, one year is quickly identified in recent fluctuations, then tens or hundreds of years in the Pleistocene, then tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands and sometimes millions of years for the oldest series, for which short cycles are difficult to identify, although they certainly existed. As the saying goes: ‘short-term cyclicity is drowned out by background noise’…. and many proxies have been ‘erased’, i.e. lost. However, thanks to the many new proxies now available and the use of appropriate mathematical processes (Fourier series, etc.), the situation is improving significantly.

Scotese et al (2021) discuss the origin of temperature fluctuations on different scales (long term >50 Ma, medium term 10-20 Ma, short term <10 Ma) and identify 24 chrono-periods (or ‘warm and cold intervals’). Among the (very) many parameters involved, the authors give priority to atmospheric CO2 content in certain intervals (particularly for the current period) as the major factor driving temperature. As is often mentioned in SCE, this factor, if it comes into play, can only be negligible. Once again, the aim here is to present curves that show that a regulated climate is meaningless, rather than a specific discussion of CO2. It should be noted that other authors, as highlighted in the article by Scotese et al (2021), report greater amplitudes of temperature variation (especially based on oxygen isotopes), but the general pattern remains the same.

…

CONCLUSION

The conclusion is simple:

There is no climate ‘change’dsiruption’, fluctuation is the rule. Geology is explicit on this point… However, despite this obvious fact, not a day goes by when the media, a politician or even a scientist talks to us about climate change.

Let’s remain objective and honest and not spread nonsense.

There’s no need for alarmism, as we’re a long way from any hot episode the Earth has ever experienced. Based on IPCC data, the authors estimate that the Earth’s global mean temperature will be between 16.5°C and 19.5°C after the current warming, meaning that the Earth will never be as warm as it was during the very warm periods it experienced. The ‘cold’ (geological scale) Late Eocene – Miocene interval is the one that seems to correspond best to the future situation.