by A. May, Feb 29, 2024 in WUWT

There are three types of scientific models, as shown in figure 1. In this series of seven posts on climate model bias we are only concerned with two of them. The first are mathematical models that utilize well established physical, and chemical processes and principles to model some part of our reality, especially the climate and the economy. The second are conceptual models that utilize scientific hypotheses and assumptions to propose an idea of how something, such as the climate, works. Conceptual models are generally tested, and hopefully validated, by creating a mathematical model. The output from the mathematical model is compared to observations and if the output matches the observations closely, the model is validated. It isn’t proven, but it is shown to be useful, and the conceptual model gains credibility.

Models are useful when used to decompose some complex natural system, such as Earth’s climate, or some portion of the system, into its underlying components and drivers. Models can be used to try and determine which of the system components and drivers are the most important under various model scenarios.

Besides being used to predict the future, or a possible future, good models should also tell us what should not happen in the future. If these events do not occur, it adds support to the hypothesis. These are the tasks that the climate models created by the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) are designed to do. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) analyzes the CMIP model results, along with other peer-reviewed research, and attempts to explain modern global warming in their reports. The most recent IPCC report is called AR6.

In the context of climate change, especially regarding the AR6 IPCC report, the term “model,” is often used as an abbreviation for a general circulation climate model. Modern computer general circulation models have been around since the 1960s, and now are huge computer programs that can run for days or longer on powerful computers. However, climate modeling has been around for more than a century, well before computers were invented. Later in this report I will briefly discuss a 19th century greenhouse gas climate model developed and published by Svante Arrhenius.

Besides modeling climate change, AR6 contains descriptions of socio-economic models that attempt to predict the impact of selected climate changes on society and the economy. In a sense, AR6, just like the previous assessment reports, is a presentation of the results of the latest iteration of their scientific models of future climate and their models of the impact of possible future climates on humanity.

Introduction

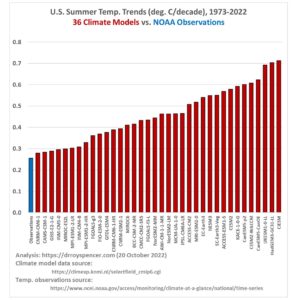

Modern atmospheric general circulation computerized climate models were first introduced in the 1960s by Syukuro Manabe and colleagues. These models, and their descendants can be useful, even though they are clearly oversimplifications of nature, and they are wrong in many respects like all models. It is a shame, but climate model results are often conflated with observations by the media and the public, when they are anything but.

…

…